Does this Product Management model work for you?

Does this work for you? – what do you think?

Regular readers will know my last two posts have been thinking about “what do product managers do?” Right now this is a pressing issue for me. Having returned to product management I’m trying to define just what it is I do. This is the model I’ve come up with (so far).

One of the things I’m keen to get away from is the idea that a Product Manager is just another version of a requirements gatherer. Yes, knowing what people want is an important part of the role and that may well mean going out and gathering them yourself. But there is more to it than that.

I’m also keen to think about the lifetime aspect of Product Management: often it is associated with the introduction of new products – all those startups! But Product is about the product.

There is a school of thought that says Product Managers replace Project Managers. While I can see why that is the two roles are not symmetrical. They address different questions so while they are both about delivering product to customers the raison d’être is different – so too are the skills and techniques they employ.

Thinking about lifetime also leads you to realise that the skills needed are going to change depending on where the product it in its life. Most obviously at the begining there is the question of market fit and at the end there is the question of end-of-life.

What does the model say?

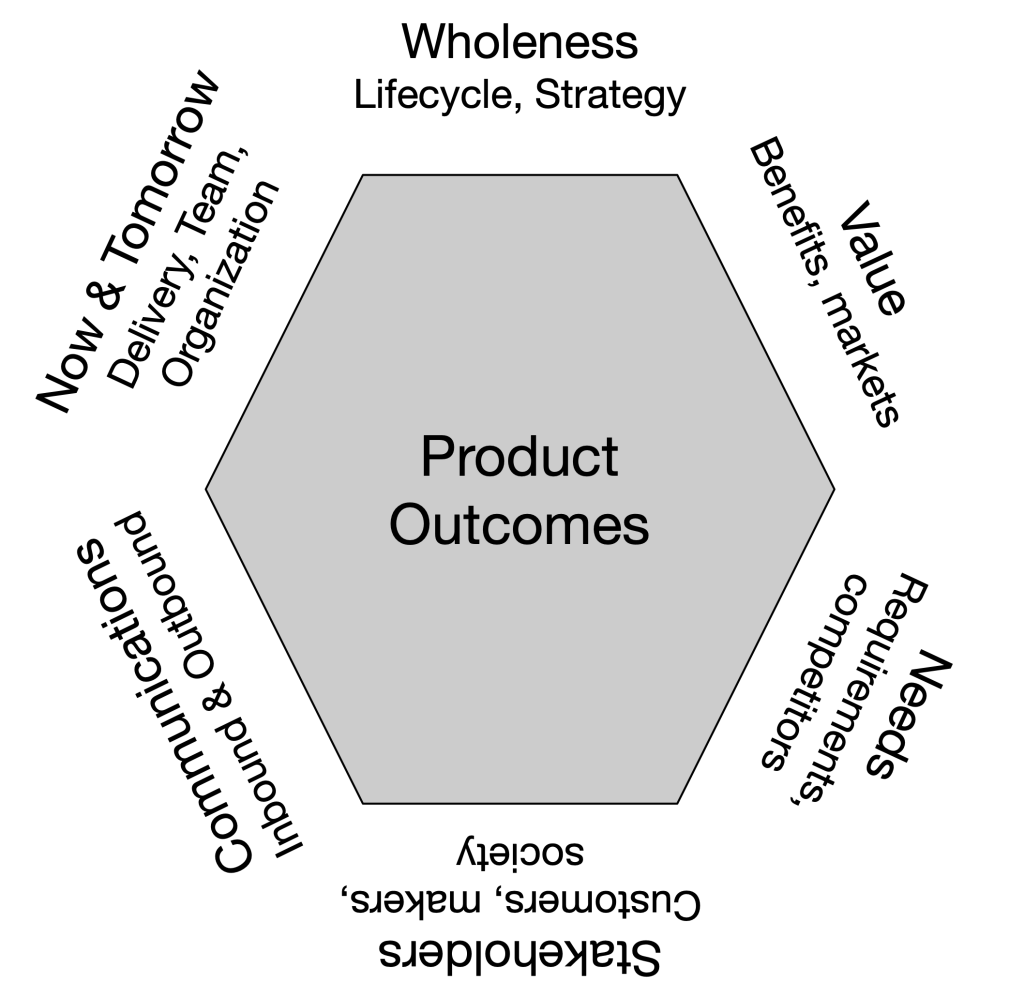

Ultimately it is about Product Outcomes – how the product changes the world, makes it a better place. However there are at least six dimensions here. I’ve labelled them above and hinted at some of the more obvious aspects of the dimension but for completeness:

• Wholeness: the Product Manager has to think about the whole product both as a thing but also over its lifecycle, that introduces time and demands strategy.

• Stakeholders: the product is only going to be meaningful if it satisfies stakeholders. For most product managers that means customers – buyers – but it also includes others in the creating organization, it might include others like regulators, ultimately it might include the whole of society. (If your strategy is move fast and break things, what happens when you break democracy?)

• Needs: product need to satisfy stakeholders needs, exactly how they satisfy those needs and whether the product is the thing that satisfies them or whether it is just a tool in a process or services needs to be understood.

• Value: if a product satisfies needs then it is valuable, that value needs to be greater than the cost of making the thing, or at least, greater than the next best thing. Value is not always money.

• Now and tomorrow: it is not enough to uncover needs, devise a strategy and write a paper on value. There is a hands on element too, this goes back to wholeness, product managers can’t be hands-off, if their brilliant ideas are going to fulfil their dreams then they can’t afford to hand-off everything. The way a product is created and delivered, the way the origanization is structured are all going to need attention. (Don’t forget Conway’s Law is lurking in the background).

• Communication: last but not least, product managers need to gather information – what do customers want? who are the competitors? what is technology doing? – and share it – what will the product do? where can you buy it? why is it better than anything else?

At the moment I think these six dimensions sum it up but I’m not sure, maybe there are just five? Or maybe there are seven? Please send me your thoughts.

An no two product managers are going to see this hexagon differently. The product itself, where it is in the lifecycle, the organization and many other factors mean that some product managers will spend most of their time in one or two dimensions, say strategy and communication, and little in others, say now & tomorrow.

Obviously, product managers working in a commercial setting are going to have very different (probably simpler) stories of how a product meets needs, generates value and satisfy customers. Those working in other settings need to be even clearer on how that all happens.

Role model?

The question on my mind at the moment is: what jobs/roles can provide a role model for product management?

(OK, this is a trick question, the role model for a product manager is another product manager but that doesn’t necessarily help generate insights.)

So far there are two that I’m attracted to and plan to write more about. For now…

First is the Toyota Chief Engineer as described in The Toyota Product Development System (Morgan and Liker, 2006).

Second up is: Poet. Yes, poet.

I’m reminded of Dick Gabriel’s description of poetry and what the poet does: it is about compressing an idea to its purest form to communicating it. Of course Dick was thinking of programming when he write about this in Patterns of Software but my intuition says it fits with product management. I’ll write more about this sometime, in the meantime you can buy Patterns of Software, or just download it for free from his DreamSongs site. (And checkout Worse is Better while you are there, a classic.)

Does this Product Management model work for you? Read More »